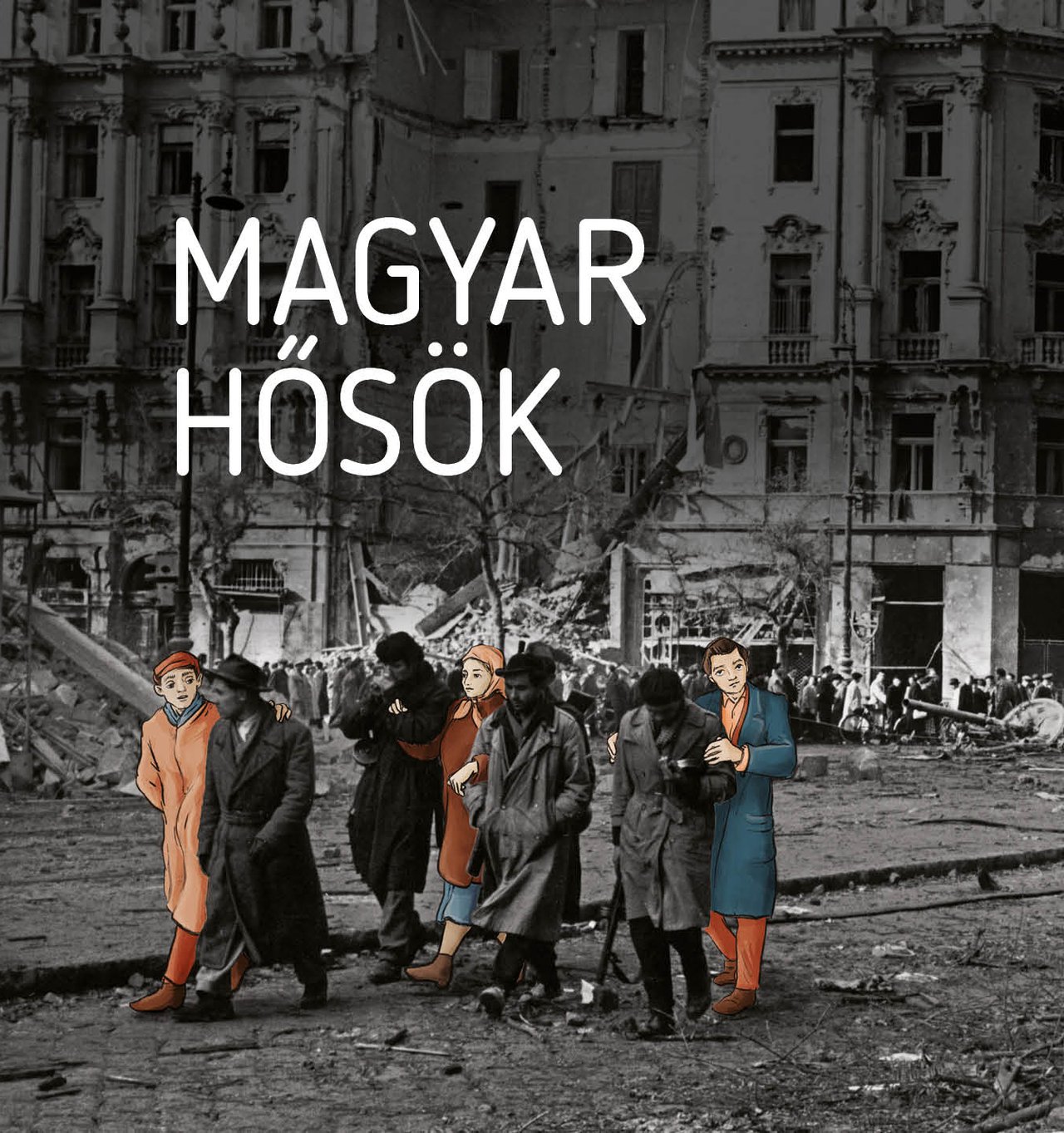

‘We wished to raise public awareness about some everyday “unsung heroes” who were either forgotten or stigmatized by Communist remembrance politics during the forty-year dictatorship,’ explains historian Réka Földváryné Kiss, chairperson of the Committee of National Remembrance, one of the editors of the book Hungarian Heroes. We sat down with Ms. Földváryné Kiss, who is also chair of the Department of Church History within the Faculty of Theology at Károli Gáspár Reformed University, to talk about heroes and victims.

When the Committee of National Remembrance was originally set up, I imagined that one of its tasks would be the publication of works such as Hungarian Heroes, published late last year. What led to the production of this book, which features sixty biographies of 20th-century individuals?

The subtitle – ‘Forgotten lives from the 20th century’ – provides the answer to how the idea for the book came about. We wanted to highlight the fact that the two totalitarian dictatorships that suppressed Hungarian society in the 20th century affected not only the level of high politics, but they also caused suffering in each and every citizen’s life. Suppressive regimes frequently forced people to make decisions that meant risking their freedom and life. The people included in the book had no ambitions of becoming heroes; they were living their lives as mayors, teachers, military officers or pastors, but at certain historic and life-changing moments they found themselves in situations when they had to make grave decisions. This risk-taking is the common thread of the stories of Hungarian Heroes.

What drove these people to take risks in such critical situations?

In the preface of the book we quote the words of Ödön Lénárd, a Piarist who was imprisoned for a total of eighteen and a half years in prisons of the Communist dictatorship: “The difference between a hero and a coward is that the hero is afraid and stays, while the coward is afraid and runs away.” What Ödön Lénárd refers to is the fact that although those who ended up becoming heroes were just as afraid of losing family, life, freedom or stability as other people, they were still willing to risk it all by making brave decisions at critical times.

How did you decide who to include in the book?

Some of them are familiar names that have been present for a while in our collective national memory, but the majority were only known in their own local or church community. By including them in the book, we wished to raise public awareness about some everyday “unsung heroes” who were either forgotten or stigmatized by Communist remembrance politics during the forty-year dictatorship. People were stigmatized through the moral smear tactics of the Communist authorities. Such fate befell the heroes of 1956, László Iván Kovács, Géza Péch or Zoltán Szobonya, just to name a few. In their case, their moral integrity also had to be restored, and so it was important to tell who they actually were and what they did. There were many attempts to suppress certain people’s life stories. The name of Géza Soos, for example, was hardly mentioned for several decades, despite the fact that he is synonymous with the history of saving human lives and resistance. Sándor Kiss and Zoltán Benkő were treated in a similar fashion. If there was no way to morally compromise them, they were at least ignored to the greatest possible extent. Our book attempts to concentrate on the main focal points of Hungary’s 20th-century history from the German occupation to the Kádár regime, in a way that encompasses the whole of the Carpathian Basin. The people featuring in the book include both right- and leftwing politicians, church people and laymen, peasants and working class people, doctors, officers and soldiers.

All of whom are linked by their heroic behaviour.

Exactly. When history forced their hand, they all behaved in a way that deserves the attention of posterity. As I have mentioned before, it is not only a member of the political, public or cultural elite that can be worthy of being called a hero, but also, for example, a village judge, namely József Bakajsza, who saved the entire male population of a small Subcarpathian settlement from forced labour, the so-called Malenki robot. Such stories are very difficult to document as often they were only recorded in the collective memory of the local community through word of mouth. It is important to write down these stories to save them from oblivion. The fact, however, that someone acted in a heroic way once does not necessarily mean that we have to agree with everything they did in their life. Certain decisions made by these paragons could be controversial, but all of them, at least at one point in their life, undertook significant risks for the benefit of their immediate or larger community, and therefore they can indeed be called heroes. Our aim was to pay tribute to these paragons of recent Hungarian history with a high-quality, richly illustrated publication, while at the same time highlighting the great dilemmas of Hungary’s 20th-century history.

What were these dilemmas?

They are the same questions we ask ourselves while reading these stories. In those given situations, what would I have done? Would I have taken the risk? Would I have been willing, like Géza Soos was, to leave behind three children and a pregnant wife and go into hiding to save my fellows? Would I have been able to, like Ilona Honti, widow of a recently executed ’56 revolutionary, to carry on as a young mother, facing years of unemployment, and stay forever faithful to the memory of my husband?

As a person of faith, it was uplifting to read stories of individuals standing up for their religious convictions.

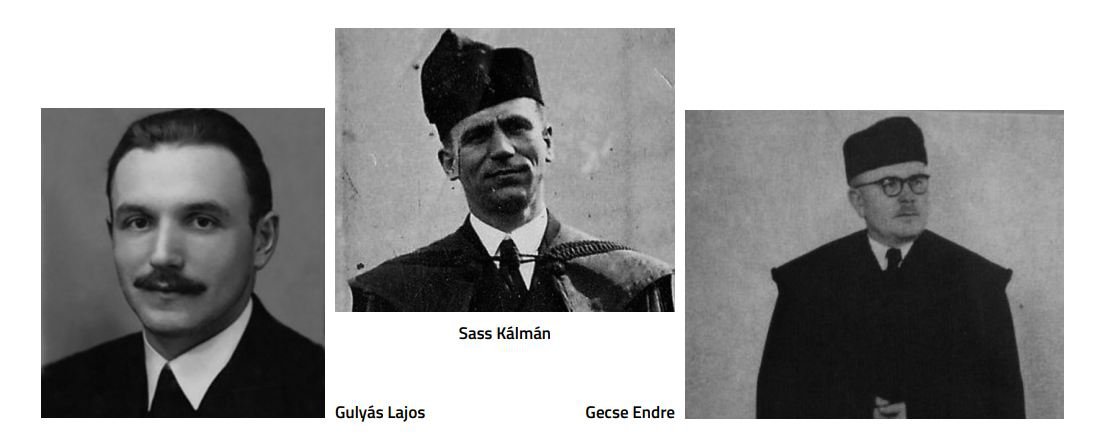

Several church-affiliated people were included in the book, who represent various denominations. Károly Dobos, for example, hid Jewish people from the authorities, and during the persecution of so-called kulaks and the forced relocation of Budapest citizens, he, together with Dean Imre Szabó, spoke out in support of those being suppressed and forced to leave their homes. But from the Reformed Church I could also mention Géza Soos of the SDG community, who was a leading figure of the resistance, or Sándor Kiss, as well as the martyred pastors of ’56, Endre Gecse from Subcarpathia, Kálmán Sass from Érmellék or Lajos Gulyás from Levél. Many of them have not received the level of attention that they would deserve even in church remembrance, despite their fascinating and deeply moving stories. We did our best to free them from the pigeonhole of church martyrdom, emphasizing that their stories form an integral part of our common national memory as well.

Another integral part of our common national memory is the 1947 Soviet deportation of Béla Kovács, general secretary of the Smallholders Party. For the past twenty years, to commemorate this event, 25 February has been the Memorial Day for the Victims of Communism. How could such a blatant violation of the law happen at the time?

Béla Kovács, head of the leading political party in Hungarian Parliament was basically kidnapped by the political police of the forces occupying Hungary, despite his parliamentary immunity. This clearly shows that Hungary did not regain its independence after 1945. With the benefit of hindsight we can say that the Hungarian Communist Party was intent on achieving autocracy right after the war, and step by step – with strong support from Soviets – was able to gain totalitarian power. Consequently it is a false narrative that between 1945 and 1948 there was parliamentary, or as some people put it, “people’s” democracy in Hungary.

This means that the Béla Kovács incident cannot be considered the beginning of the Communist seizure of power.

Indeed, the kidnapping of the general secretary of the Smallholders Party was just one moment in a series of events. But the story of Zoltán Benkő, which also features in our book, is just as important. Benkő was one of the young intellectuals who took part in the resistance movement and the saving of human lives, and whose personal qualities would have made them play a leading role in the formation of a civic democratic Hungary. This group of talented and ambitious people was marginalized early on. The real aim, therefore, was to break up this democratic elite, and the events of kidnapping Béla Kovács, and forcing Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy into emigration, were the climaxes of this process. Some were imprisoned, sent to forced labour camps or had to emigrate, while others were cornered into collaboration with the authorities. Benkő, who had earlier taken up arms to fight the far-right Arrow Cross Party, was arrested in 1945, 1947 and 1948 and was accused of being a Fascist. Rumour has it that when he asked how on earth he could be a Fascist when he took part in blowing up the statue of Gömbös, the interrogating officer replied that if one was capable of blowing up things in 1944, one is also able to do so after 1945. This clearly shows that the Communists were most afraid of those who in the past had the fortitude to stand up against far-right dictatorships, and considered them to be the true enemy.

Is it not in fact true that anyone could become a victim of the dictatorship?

On the one hand, the Communist Party constantly expanded the scope of its enemies. Anyone who could even remotely be suspected of possibly endangering their power was accused of being anti-Communist, or even Fascist. If someone was a member of an autonomous community capable of forming their own opinions and making their own decisions, with a clear system of values, they were considered to be dangerous. In the spirit of this attitude, the party struck down on the property-owning segments of society, churches and civil associations. On the other hand, despite all of this, Hungarian society refused to completely subjugate themselves to the Communist power. Resistance took a variety of forms. When, for example, all religious meetings outside churches were banned, holding a Bible study was an act of cultural resistance. In the Rákosi era even such phenomena were handled with violent means. And we should bear in mind that despite the havoc totalitarian dictatorships wreaked on the intellectual elite, the year 1956 saw the emergence of a group of young leaders who were able to guide local communities in a responsible way. This shows that Hungarian society had a lot of reserves to rely on. When we talk about the situation, humiliation and compromising nature of Hungarians, we must also mention that some chose loyalty, quiet resistance and risk-taking.

Some people today are very quick to label something a dictatorship, for one reason or another. Does this mean we have to keep explaining what constitutes a dictatorship and what does not?

It is indeed really important to use such terms correctly. One of the messages of Hungarian Heroes is the fact that these terms can wear out if we overuse them needlessly. If we deem every political system a dictatorship that is not in line with our own values, we diminish the risk-taking of the people featuring in the book and those who acted in a similar way. A dictatorship is an autocracy in which the state relies on violent police forces while at the same time ignoring the law, in order to enforce its suppressive power in every aspect of life, arbitrarily taking individuals’ lives and freedom. To fight against such powers meant truly risking one’s freedom and life. The weight of this must not be forgotten, and the significance of people’s heroic risk-taking and brave decision-making should never be lost.