We often hear about the disadvantages women have faced throughout history - we need only recall the lack of voting rights or forced marriages. Only on rare occasions, however, is it discussed that they have played a crucial role in shaping history even within these constraints. Their contribution was not only significant but essential to the progress that has led to the equality and mutual respect we enjoy today. This was also the case in the history of the Hungarian Reformed Church: there are many undeservedly little-known but undeniably outstanding women. The following are a few examples without claiming to be exhaustive.

In the pre-Reformation period, the medieval Catholic Church set a firm framework for the religious and social role of women. The church hierarchy consisted almost exclusively of men. The monastic life was one of the few exceptions, giving women the opportunity to learn, cultivate and enjoy a degree of autonomy. Among the nuns who lived in medieval European monasteries, Hildegard of Bingen, for example, left a lasting mark through her spiritual and scientific writings.

The religious life of secular women was mainly confined to family and charitable roles, their influence remained indirect, while the church reinforced the ideal of the faithful wife and caring mother. The Reformation brought new opportunities, promoting a more active practice of faith and access to education for all. The 16th-century Reformation emphasised Bible reading and education in the mother tongue so that girls could also benefit from a wider range of religious and secular education. In addition, the wives of many Protestant pastors and theologians - such as Martin Luther's wife Katharina von Bora and John Calvin's wife Idelette de Bure - actively supported their husbands, helping to spread the ideas of the Reformation.

ZSUZSANNA LORÁNTFFY: PATRON OF EDUCATION

Zsuzsanna Lorántffy's life was a mixture of war, politics and religious commitment. As a leading figure of the mid-17th century, she not only supported her husband, György Rákóczi I., prince of Transylvania but also played a significant role in shaping Hungarian and European culture.

Statue of Zsuzsanna Lórántffy in Sárospatak

Zsuzsanna Lorántffy, born in 1602 in Ónod, married the Prince of Transylvania when she was only 14, thus combining the wealth and power of two important families. Their marriage brought significant political and religious changes, as the Rákóczi family became one of the most influential rulers in Upper Hungary.

After her husband's death in 1648, she distinguished herself not only as a land administrator but also as a patron of the arts. The princess was famous for growing herbs in her gardens to cure the sick and for her embroideries, which she contributed to the beautification of Reformed churches, including a tablecloth, which is part of the exhibition of the Reformed Museum in Sárospatak. She devoted special attention to academic and religious life. In 1650, she invited the famous philosopher and pedagogue Comenius to reform the education of the ancient school in Sárospatak, which thus became a key element in the Hungarian Reformed school and religious life.

Zsuzsanna Lorántffy's authentic religious life and biblical knowledge also won her recognition among scholars and priests of the time. In addition to her sincere and profound religiosity, which reflected the spirit of Puritanism, she often defied the political decisions of the princely court and defended the Reformed religious doctrines. She also published two works on ecclesiastical subjects, which were bibliographical collections that contributed to the spread of contemporary Christian scholarship.

In the last decades of her life, despite family tragedies, she found joy in supporting the church and school. Her intellectual legacy in the fields of science and religion continues to define the Hungarian Reformed tradition and the history of religious culture.

KATA BETHLEN: FOR FAITH THROUGH THE POWER OF LITERATURE

The life of Kata Bethlen, by cognomen the Orphan, one of the most prominent female figures of the Transylvanian Baroque period, was full of tragic twists and turns, yet her extraordinary work and religious commitment left an everlasting mark on the history of the Hungarian Reformed community.

Born in 1700, Kata Bethlen was widowed at a young age, having lost two husbands and several children. Her greatest support in life was writing and engaging in scientific work. In 1744, she began her autobiography, which reflects some of the most difficult times in her life. Her memoir combines the events of her life with biblical pathos and direct language in a unique blend of autobiography and diary. Her work was published after her death in 1762 and remains an important literary and historical source.

Kata Bethlen

Like Zsuzsa Lorántffy, she was a prominent patron of the arts in addition to her writing career. Kata Bethlen supported several Reformed colleges in Transylvania, donated books and published several works at her own expense. She herself built up a rich library, which she bequeathed to the Reformed College of Nagyenyed in her testament. Unfortunately, the collection was destroyed during the War of Independence (1848/49). Nevertheless, Kata Bethlen made a lasting contribution as a defender of the Reformed faith and a supporter of Hungarian culture. Her life and writings made her one of the greatest female figures in Baroque literature.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw a significant change in the role of women in the Reformed Church, particularly in the areas of education, diaconal service and social responsibility. The first Reformed women's organisations were founded, which did important work in education, charity and community organisation. The issue of women's ministry became topical in the 20th century, and in many countries, women were allowed to be ordained and thus actively participate in church leadership.

MÁRIA MOLNÁR: THE MODERN-DAY MARTYR

Mária Molnár, whose name may sound familiar to many, was born in 1886 in Várpalota as a child of a family of millers. It was in Budapest that she encountered the depth of the Reformed faith when she came into contact with the Bethany Society. Her passion for nursing and helping people soon found a way: she became a member of the Filadelfia Deaconess Society and started working at Bethesda Hospital, which is also operated today by the Reformed Church in Hungary.

Mária Molnár

During the First World War, she nursed wounded soldiers - first in the hinterland and then in Galicia, near the front line. She was also awarded the Red Cross Medal and the Silver Cross of the Crown for her bravery. After the war, she continued her ministry in Győr, but this time, she did not only work in the medical field but also gave Bible lessons, did youth work, and visited prisons and hospitals. She even did pastoral care among street girls and those attempting suicide.

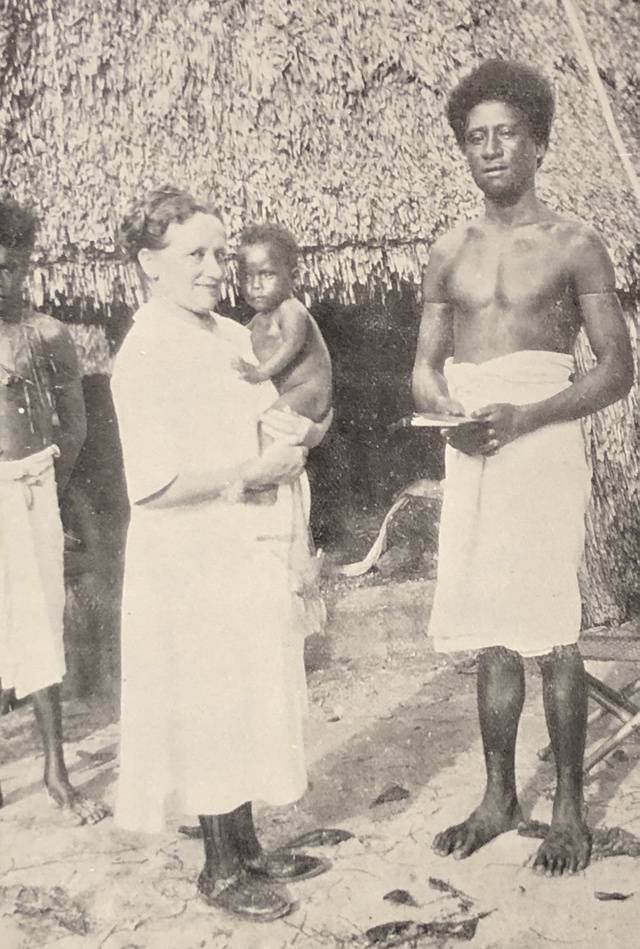

Mária Molnár had no plans for missionary work outside of the country, as she thought she had enough to do in Hungary. But in 1925, while listening to a missionary's report, an inner voice told her that she should engage in wider mission. While she was frightened of the tropical climate and the distance, she was even more afraid of not following God's will. At her release service, she said goodbye with the following words: “I do not pray for I may not be dropped into the sea, or that cannibals may not devour me, but that I may remain faithful to Christ to the end.” She arrived on the island of Manus in 1928, where she continued her work as a teacher and healer and was known locally as “Misses Doctor.” Japanese troops invaded the islands in 1942. Mária Molnár was offered the chance to escape, but she stayed and was executed by the Japanese in 1943.

The life and death of Mária Molnár is not just the story of a distant foreign mission but an example of faith and dedication. She was the Hungarian Reformed woman who gave up everything to serve others - and ultimately gave her most precious treasure, her life, for the mission.

KLÁRA TÜDŐS: A MULTITALENTED CREATOR

The name of Klára Tüdős (Mrs. Zsindely) does not shine on the pages of history textbooks, although her life and work left a remarkable mark on the history of Hungarian culture and society. She was at once a fashion designer, ethnographer, film director and memoirist, but her primary mission in life was always to serve the community.

Klára Tüdős in 1940

She was born in 1895 in Debrecen in a family marked by a liberal spirit. She began her studies at the Dóczy Institute in Debrecen, a reformed secondary school for girls. She then continued her studies in London and Switzerland. In 1925, she became head of the costume workshop of the Opera House, but in the 1930s, she devoted most of her attention to modernising folk motifs and traditional Hungarian costumes. As a result, she opened her fashion salon. The Pántlika (Ribbon) Salon became known as a fashion shop and an important centre of social life. The shows there became real social events, and famous Hungarian ladies appeared in dresses designed by Klára Tüdős.

Her versatility was manifested by the fact that she became Hungary's first female film director in 1943 when she produced the movie “Light and Shadow”, in which she was the director, scriptwriter, and costume designer. In her films and writings, she emphasised preserving Hungarian cultural heritage and social responsibility.

“I know that God grants his goods and treasures of all kinds here and there and that our only duty is to make sure that none of them, material or spiritual gifts, are stuck with us.” This faith, which accompanied her throughout her life, was also reflected in her service to people. During World War II, as president of the National Reformed Women’s Association, she gave refuge to many persecuted people, including Jews and political refugees. At her home, the Zsindely Villa, Santa Claus celebrations were held for children while adults read the Bible together. The love and community spirit of Klára Tüdős Zsindely proved in these difficult days did not diminish after the communist takeover. After she and her husband relocated to Balatonlelle, a village at Lake Balaton, she saw her task in creating a new home and establishing and strengthening the local Reformed community life.

She was much more than a simple fashion designer: she was an important figure in Hungarian culture and community life who dedicated her life to serving others. It is not by chance that her works are kept in the Museum of Applied Arts, the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest and the Déri Museum in Debrecen. Her work and faith have left a lasting mark, and her legacy still lives on today.

These women were examples of commitment, perseverance and faith. It is important to remember them today so that we can learn from them and get inspiration from their example.